Understanding Set-Point Theory: Exploring Weight Regulation

What is Set Point Theory? Set-point Theory is a theory that suggests our bodies have a natural weight range where they function optimally. This concept is crucial in understanding how factors like genetics, diet history, hormonal changes, and aging influence our body weight. As dietitians, we delve into how this theory impacts our approach to nutrition and health.

Your body will adapt to maintain that weight without much resistance, even when subtle change occurs. Many factors, such as genetics, dieting history, hormonal changes, and aging, can affect your set-point range. This topic tends to bring up a lot of feelings, fears, and opinions as it can be challenging to accept amidst our diet- and weight-centric culture. Set-point theory explains why weight loss often cannot be sustained over a long period of time. Set-point theory suggests that the body resists weight change by putting into place compensatory mechanisms.

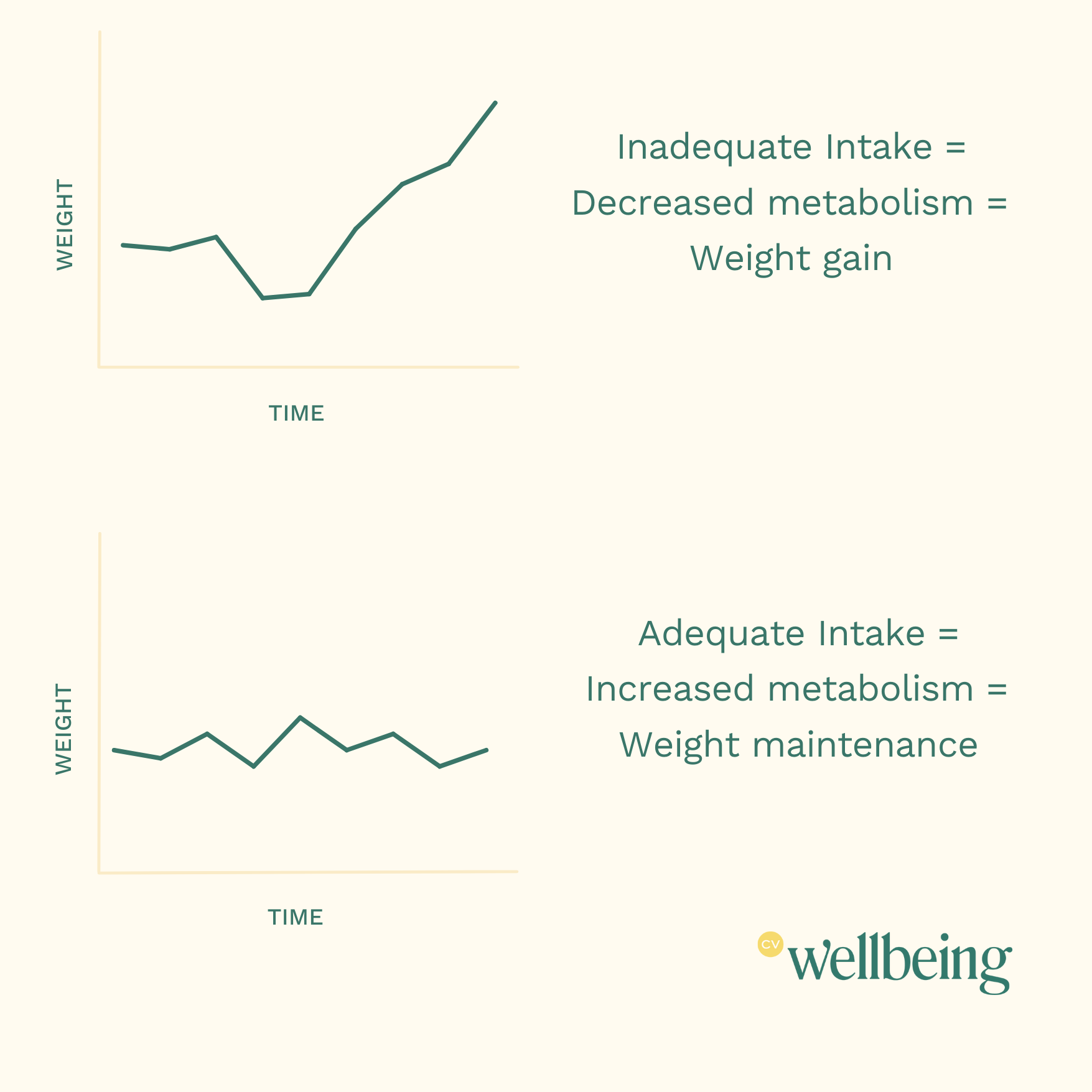

Essentially, your body will adjust to periods of more food and less food to keep your body weight stable.

Understanding the Effect of Set-Point Theory on Weight Regulation

One of the ways your body adapts is by shifting hormones. During food deprivation, cortisol levels rise (stress hormone), leptin levels drop (fullness hormone), and ghrelin levels increase (hunger hormone). This causes those in a deprived state to feel hungrier, and the hunger will remain even after eating a meal.

-

Ghrelin, commonly known as the "hunger hormone," is a key player in appetite regulation. Produced mainly in the stomach, ghrelin sends signals to the brain to increase hunger and stimulate food intake. Ghrelin levels naturally rise before meals and decrease after eating, making it essential for understanding hunger cues

-

Leptin, also called the "fullness hormone," is a hormone secreted by fat cells that helps regulate energy balance by reducing appetite. It communicates with the brain to signal when the body has enough stored energy, helping to prevent overeating. Leptin resistance, a condition where the brain stops responding to leptin signals, can contribute to weight gain and difficulty feeling satisfied after meals.

-

Cortisol is a stress hormone produced by the adrenal glands that impacts numerous bodily functions, including metabolism, blood sugar regulation, and inflammation. Often referred to as the "stress hormone," cortisol is released during times of stress to prepare the body for a fight-or-flight response. However, chronic high cortisol levels can disrupt hunger cues, lead to increased cravings.

Along with these hormonal changes, there is an overall reduction in energy expenditure. This is because your body's metabolism slows down in an effort to survive. Your body registers a famine, leading to an override of a few of its "non-essential" mechanisms. One of the mechanisms altered in restriction includes thermal regulation. Those in a deprived state might notice that they are consistently cold when others around them are not or have cold hands and feet (this is your body conserving and pulling heat to warm your organs because that is more important than the extremities). Those in a deprived state might also notice that their digestion is off, tending to feel more bloated or constipated than usual.

The Minnesota Starvation Project: A Lesson in Body Weight Regulation

Another way that the body responds to starvation and tries to keep you motivated for food is by increasing the reward value of food.4 It does this by changing various cognitive and attentional functions, which cause you to become hyper-focused or obsessed with food. An example of this process is outlined in the Minnesota Starvation Project conducted in 1944 on 36 men who were put on a restrictive diet of 1,400-1,600 calories/day (*Note: I find this interesting; this is not typically the calorie range that you may perceive as starving). While extremely unethical, this study gave us much insight into what happens during starvation.

As the men lost weight, besides the physical side effects of hunger (which were profound), they also became obsessed with food. Men began reading cookbooks, staying up late to look through recipes, and some even considered changing career paths to one related to food. The obsessions continued for months and some years after being refed. Studies confirm this effect by assessing different attentional focus tests, such as eye tracking methods, the attentional blink paradigm, or dot-probe tasks. The studies find that people's attention is biased toward food stimuli when calorie-deprived. Brain imaging studies also find increased brain activity in areas that control attention in calorie-deprived individuals when shown images of palatable foods. Studies have also found that smell functioning and palatability of foods increase when calorie-deprived.

In food restriction, uncertainty about food supply triggers an adaptive response to gain weight, similar to what our ancestors would have experienced during times of variable abundance and scarcity.

To summarize, these are all ways our body responds to a restricted state.

Hormones shift: An increase in cortisol levels (the stress hormone), a decrease in levels of leptin (the hormone that tells your body it's full), and an increase in levels of ghrelin (the hunger hormone) occur.

Thermal regulation: Feeling constantly cold when others around them are not or have cold hands and feet because your body is conserving and pulling heat to warm your organs.

Digestion: Those in a deprived state might notice their digestion is off. They feel bloated often or may experience constipation.

Metabolism: Weight loss produces metabolic shifts that favor lipid storage.

Neurological changes: The attention centers of your brain shift towards food, leading to an obsession or preoccupation with food. The brain's reward center sends a more substantial response when we eat. Smell functioning and palatability increase.

Finding Your Set-Point Weight

There is no one equation, chart, or test to determine where your natural set point weight is. Your unique genetic blueprint determines this, which is why we humans could all eat the same and still have body diversity. Collectively, when we are at our set-point weight (excluding that we do not have a chronic illness or underlying medical issues, and our hormones are balanced), our labs are stable, our hair and nails are strong, our hunger and fullness cues are present, and it is effortless to maintain our weight. Effortless means we don’t count calories, restrict foods in any way, try the new diet fad, exercise to “burn off” what we’ve eaten, or constantly overthink food choices.

It is essential to point out that being at a healthy weight for you doesn’t necessarily mean “healthy” for others. One study showed that 38% of patients who were restricting calories lost their periods while still at a “normal BMI,” as many exhibited symptoms of starvation without being clinically underweight. To learn more about BMI (and why it's not very good science), check out our blog post here.

We can discover our true set-point weight by letting go of the sense of control with food and our body and instead trusting that our body will know where to land. According to research, the weight at which our bodies settle (set-point weight) is 70% genetic. (To compare this, our height is 80% genetic). This process requires time, patience, and a lot of self-compassion. Working with a HAES and intuitive eating dietitian can support you through this process.

Discovering your body's natural weight using set point theory requires letting go of the rigid control over food and trusting your body's innate wisdom. This journey demands patience, self-compassion, and the guidance of a knowledgeable dietitian. If you're seeking to understand your body's natural weight regulation and develop a healthier relationship with food, our team at CV Wellbeing is here to support you. Contact us for personalized and HAES-aligned nutrition counseling.

Set-Point Theory FAQs

-

Set-point theory suggests that each person has a natural weight range that the body is programmed to maintain, where it functions best. This weight range is influenced by genetics, biology, and environmental factors, not willpower or dieting.

-

When weight deviates from the set point, the body uses mechanisms—like altering metabolism, adjusting hunger and fullness cues, or releasing specific hormones—to return to this range. These adaptations help keep the body stable, prioritizing survival over intentional weight change.

-

While some factors, like significant lifestyle changes, trauma, or prolonged illness, can cause the set point to shift, it’s generally a stable range. Dieting often causes temporary shifts, but once normal eating patterns resume, most people return to their set-point range.

-

No, set point weights vary widely and are influenced by genetics, early life experiences, and lifestyle. This range may not align with societal or cultural standards but is where each individual body feels and functions best.

-

Instead of weight as a primary goal, consider behaviors that enhance health and well-being. Research suggests that repeatedly trying to lower weight below the set point can strain the body, making sustained weight loss challenging and potentially harmful.

Written by Alison Swiggard, MS, RDN, LD & Lauren Hebert, MS, RDN, LD, Registered Dietitian Nutritionists at CV Wellbeing

510 Main Street, Suite 103, Gorham, ME 04038

Like this post? Share it here!